Internal Mammary Perforator Preserving Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy (IMP-NSM) to Reduce Ischemic Complications

Abstract

Nipple-Sparing Mastectomies (NSMs) with breast reconstruction are commonly performed for both breast cancer treatment or risk-reducing prophylactic mastectomies and have superior aesthetic results compared to total mastectomy or skin-sparing mastectomy. Preservation of the Nipple Areolar Complex (NAC) results in a more natural aesthetic appearance of the reconstructed breast, as well as greater patient satisfaction, as indicated by improved psychosocial and sexual well-being compared to total mastectomy. Preservation of vascular supply is of utmost importance for NAC and mastectomy skin flap viability after surgery, since postoperative ischemic complications can significantly undermine the aesthetic outcomes.

This report describes a contemporary NSM surgical technique developed by the senior author (MK), to preserve the dominant NAC vascular supply, and decrease postoperative ischemic complications. A total of 114 NSM were performed from 2018 to 2020 by the senior author. Based on preoperative breast MRI with contrast visualization of the vascular supply to the NAC, the Internal Mammary Perforator (IMP) vessels exiting the pectoralis major muscle at the sternal border were found to provide the dominant blood supply to the NAC in 92% and could be preserved in 89% of cases.

The Internal Mammary Perforator Preserving Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy (IMP-NSM) surgical technique was developed to preserve this important IMP blood supply to the NAC, resulting in decreased postoperative ischemic complications. Following implementation of this surgical technique, NAC necrosis requiring NAC removal occurred in 0.9%, and mastectomy skin necrosis requiring reoperation in 1.8% of cases, resulting in successful NAC preservation in the majority of patients. Furthermore, due to the consistent anatomical location of the IMP vascular supply to the NAC, this critical vascular supply can routinely be preserved even without preoperative MRI, thereby improving clinical outcomes. The IMP-NSM surgical technique is described in detail in this report with a case example.

Keywords

Internal mammary perforator; nipple-sparing mastectomy ischemia, Nipple-sparing mastectomy necrosis; perfusion; nipple areolar complex.

Case Overview

Background

Nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) with immediate breast reconstruction results in improved appearance of the reconstructed breast and greater patient satisfaction compared to total mastectomy.1–6 Although NSM techniques have been described to preserve all the breast skin and nipple areola complex (NAC), postoperative ischemic complications (i.e., necrosis) requiring reoperation and excision of necrotic skin or NAC represents a significant complication commonly reported with conventional NSM, which does not specifically preserve the blood supply to the NAC.7–10 Therefore, specific methods to preserve the blood supply to the NAC and mastectomy skin can decrease ischemic complications, and significantly improve patient outcomes.

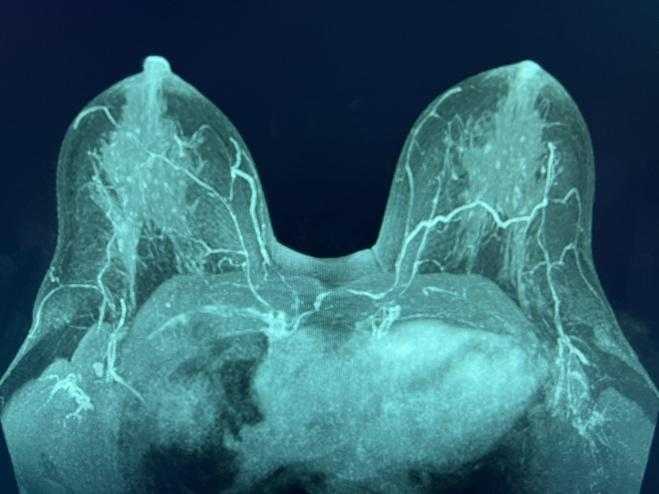

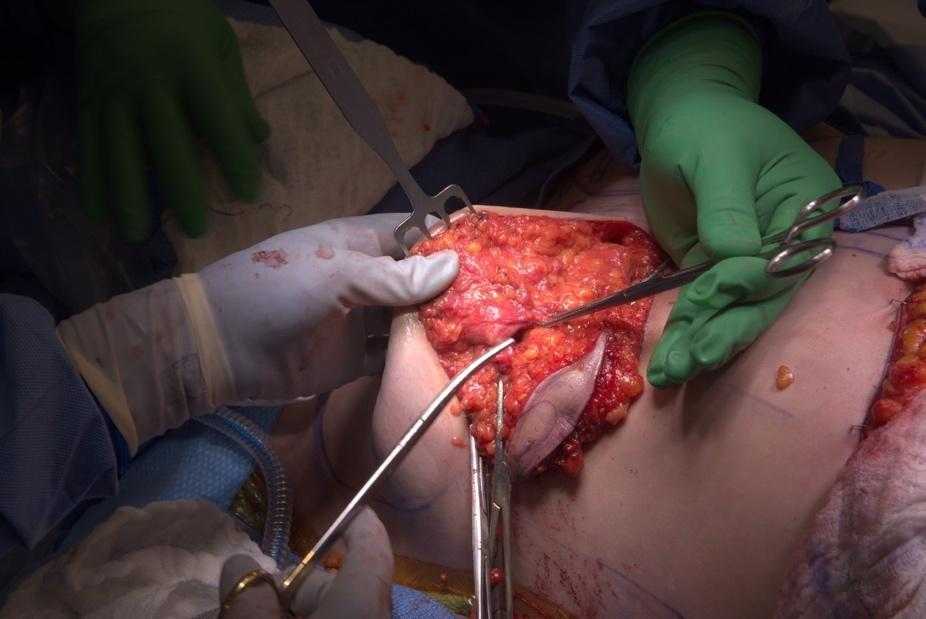

The development of the Internal Mammary Perforator Preserving Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy (IMP-NSM) surgical technique by Karin is based on a consistent vascular pattern and preserves the dominant blood supply to the NAC, which originates from the IMP vessels exiting the pectoralis major muscle at the sternal border in the majority of patients (Figure 1). Preservation of this vascular axis will predictably result in decreased ischemic complications.1, 1113 Furthermore, with IMP preservation, the associated anterior cutaneous sensory branches (ACB) of the intercostal nerves (ICN), which travel with the IMP vessels and provide sensation to the medial breast and NAC, are often observed and preserved (Figure 2), thus holding promise for preserving sensation to a greater degree than following conventional mastectomy techniques.14 The important steps of IMP-NSM including the retroareolar dissection, subnipple biopsy, mastectomy flaps, and dissection for IMP preservation, are described in detail in this report with a case example.15, 16

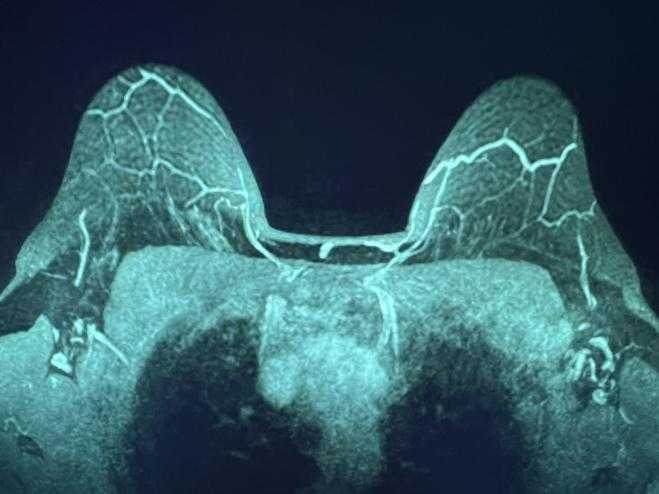

Figure 1. MRI MIP demonstrating the IMPs traveling to the NAC, superior to the nipple (left) and at the level of the nipple (right).

Figure 2. Examples of IMP neurovascular bundle with artery, vein, and ACBs of sensory nerve at 3rd ICS preserved in mastectomy flap during IMP-NSM.

Focused History of the Patient

A 58-year-old postmenopausal female presented with mammographically detected right breast Grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma, estrogen receptor (ER) negative, progesterone receptor (PR) negative, and HER2 positive, with Ki67 of 70–80%, indicating a very fast proliferation rate. Screening mammogram demonstrated right breast asymmetry with associated calcifications. Diagnostic mammogram with ultrasound (US) showed a 0.9-cm suspicious mass at 6:00, 8 cm from the nipple (cmfn). An US-guided core needle biopsy confirmed the results above. Due to a family history of breast cancer—mother at age 78, and sister at age 50—and father with prostate cancer, a genetic testing panel for hereditary breast cancer was obtained and was negative.

Breast MRI was performed for staging, which demonstrated the known biopsy-proven cancer, measuring 1.8 cm at 6:00, and findings suspicious for multifocal disease, including other suspicious abnormalities at 6:00, and a very suspicious 1.3-cm abnormality at 3:00. No palpable or abnormal lymph nodes on imaging. Initial clinical stage was cT1c(multifocal) N0.

The patient was generally healthy with a BMI of 30.2 kg/m2, and ASA class 3. She quit smoking 6 years prior to surgery and had a 3.75 pack-year smoking history.

Physical Exam

Physical exam findings included preoperative bra size 38C with grade 2 ptosis. The known right breast cancer was palpable as a firm, irregular approximately 2-cm mass just superior to the inframammary fold (IMF), close to the overlying skin, and right breast tenderness at 6:00, 2.5 cmfn with firmness, possible needle biopsy swelling vs. mass. The right NAC appeared normal, the left nipple was partially inverted, without discharge bilaterally. No palpable lymph nodes.

Imaging

Breast MRI with contrast obtained for staging, demonstrated a 1.8-cm known right breast cancer at 6:00, 9 cmfn near the skin of the IMF, 2 additional suspicious small masses 2.3 cm more superiorly, a suspicious 1.3-cm area at 3:00, and no suspicious lymph nodes.

The breast MRI MIP (maximal intensity projection) images, a common reformat averaging multiple slices, clearly visualized the dominant blood supply to the NAC (Figure 1). Bilateral dominant IMPs, emanated from the pectoralis major muscle along the sternal border at the 2nd and/or 3rd intercostal spaces (ICS). Thereafter, the vessels coursed anteriorly in the subcutaneous tissue of the breast and terminated near the NAC.

PET CT, performed after the postoperative diagnosis of lymph node metastasis, showed no distant metastasis.

Options for Treatment

The patient was evaluated by medical oncology regarding the options of neoadjuvant vs. adjuvant chemotherapy with HER2 targeted treatment and based on the initial clinical stage, surgery was recommended first. The standard systemic treatment was a combination of chemotherapy and HER2-directed therapy. Due to the heterogeneity of HER2 disease, the chemotherapy would treat the portions of the disease that were not HER2 positive.

The patient was offered breast conservation treatment as well as mastectomy (nipple-sparing) with immediate reconstruction.

Based on the imaging findings and a strong family history of breast cancer, she decided to proceed with bilateral mastectomies and desired a nipple-sparing approach with immediate breast reconstruction.

Reconstructive options offered were implant-based reconstruction as well as autologous reconstruction. Following a thorough discussion, the patient opted for bilateral autologous reconstruction with free abdominal flaps.

Rationale for Treatment

The goals of surgical treatment included cancer removal with clear margins. This was achieved via bilateral IMP-NSM, axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), and completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) performed for SLNB macrometastasis and several suspicious palpable lymph nodes intraoperatively. Final pathologic stage was pT2N3a (cancer in 15/26 LN’s). She received adjuvant ddAC-Taxol and Herceptin, and adjuvant radiation therapy (RT) (50 Gy over 5 weeks), treating the right reconstructed breast and all regional nodes using a 3D conformal radiotherapy technique.

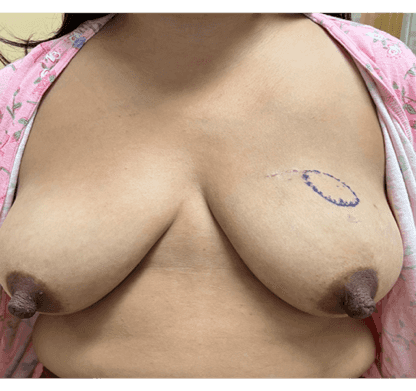

The right subnipple biopsy was read as benign intraoperatively; however, final pathology showed carcinoma in lymphovascular spaces and at the nipple base. Therefore, the right nipple was subsequently excised, converting the procedure to a right areola-sparing mastectomy (ASM) (Figure 3). She developed partial areolar necrosis inferiorly and inferior mastectomy skin necrosis superior to the IMF bilaterally (presumably related to retraction), which healed with local wound care. For the inferior areolar hypopigmentation, matching the surrounding color with an areolar tattoo was offered, but she declined being satisfied with the appearance. This demonstrates the aesthetic appearance following ASM and NSM, with immediate breast reconstruction, which results in a natural breast contour, that is superior to what can be achieved with total mastectomies.

Figure 3. Left: IMP-NSM dissection demonstrating the IMP preserved, corresponding to above MRI in Figure 1. Right: Post-op photo at 3 months after bilateral IMP-NSM and immediate abdominal free flap breast reconstruction with right muscle-sparing transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap (MS-TRAM) and left deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap. Subsequent right nipple excision for cancer in subnipple biopsy, and healed following conversion to right ASM, and partial areolar/skin necrosis inferiorly.

Special Considerations/Surgical Technique IMP-NSM

The IMP-NSM surgical technique to preserve important NAC blood supply, has been previously published including the major important steps.1, 11, 12 Breast MRI with contrast, if obtained for preoperative staging, can clearly demonstrate the NAC blood supply, best visualized on MIP images. This shows the dominant NAC blood supply typically originating from the IMP bilaterally, usually at the 2nd or 3rd ICS along the sternal border (Figure 1).

The 2nd–4th ICS are marked on the skin, 1 cm lateral to the sternal border, indicating the common areas where the main IMP vessels are identified and preserved anterior to the pectoralis major muscle. The IMP-NSM technique can be performed without breast MRI, by marking these usual locations with subsequent careful dissection in those areas; however, if available, breast MRI images can provide helpful information regarding the IMP blood supply and anticipate the location at surgery. IMP-NSM is defined as preserving the dominant IMP blood supply to the NAC; however, the technique has evolved to include preserving additional small non-dominant IMP vessels visualized along the sternal border, which can contribute to vascular supply, in addition to associated ACN sensory branches. (Figures 1 and 2).

Skin incisions are most commonly along the IMF, and in this case included skin removal overlying the largest right breast cancer close to the skin at 6:00 at the IMF. Through the skin incision, low volume dilute tumescence solution is injected into the subcutaneous tissue overlying the breast tissue (1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000, 20 cc diluted in 200 cc NS).17, 18 IMP-NSM subcutaneous flaps are elevated over the breast tissue using a combination of cautery, blunt, and sharp dissection. This is facilitated by the preceding tumescence hydrodissection. Furthermore, tumescence expands the width of the subcutaneous tissue, making it easier to dissect the mastectomy flaps with consistent optimal thickness, and avoid injury to the vascular supply to the subcutaneous tissue and skin, thereby decreasing ischemic complications.

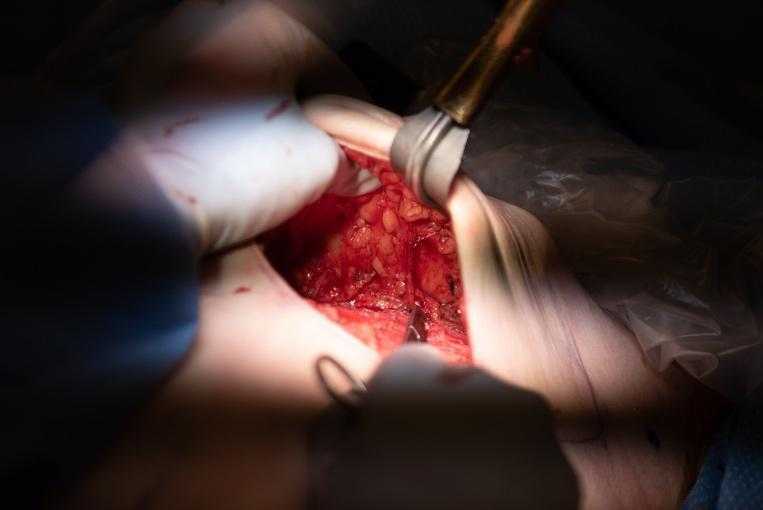

The subareolar dissection overlying the breast tissue is usually very close to the skin since the subcutaneous tissue is much thinner. Thus, Metzenbaum scissors are used for blunt and sharp dissection, and cautery is generally avoided to prevent thermal damage to the subdermal vascular plexus. The ductal bundle going to the nipple is identified circumferentially with blunt dissection (Figure 4), divided directly under the dermis of the nipple with Metzenbaum’s, and approximately 0.5–1 cm length is removed, marking the final anterior margin under the dermis of the nipple with a suture. The subnipple biopsy is sent to pathology for intraoperative evaluation, to ensure that the nipple is free of any malignant pathology.

Figure 4. Subnipple biopsy-ductal bundle supplying the nipple circumferentially. Division of ductal tissue with Metzenbaums, directly underneath the dermis.

The critical step for IMP-NSM is very careful and gentle dissection with IMP preservation near the sternal border, usually at the 2nd and 3rd ICS where the dominant IMP typically perforates the pectoralis major muscle and then courses in the subcutaneous tissues (Figure 3). Smaller IMP blood vessels are often observed at other ICS and preserved if identified. The tumescence facilitates this dissection, and with gentle spreading with a clamp, the breast tissue is easily separated from the subcutaneous tissue containing the IMP, with IMP preservation (Figures 2 and 3). Dissection to preserve the dominant IMP is facilitated with visualization of the 2nd–3rd ICS near the sternal border, usually after the remainder of the mastectomy dissection is mostly completed.

Surgeon placed pectoralis (PECS) regional blocks are typically injected under direct visualization. Bupivacaine with epinephrine is injected as follows: PECS1 (10 cc under fascia between pectoralis major and minor), PECS2 (10 cc under the fascia between the pectoralis minor and serratus) and 10 cc, or the remainder, as a serratus plane block under the exposed serratus fascia and field block.

Discussion

This report describes the IMP-NSM surgical technique, developed specifically to decrease ischemic complications by preserving the important IMP, which provides the dominant blood supply to the NAC in 92% based on breast MRI.1 Prior descriptions noted IMP-dominant NAC blood supply in the majority of patients, in addition to contributions from the lateral thoracic artery.19 Amanti stated that preserving IMP cutaneous branches is of utmost importance for NAC viability with NSM.20 Importantly, based on breast MRI blood supply patterns, the IMP contributes to NAC vascular supply, even if not the dominant blood supply, and therefore preservation is attempted in all IMP-NSM to help prevent necrosis. Despite reports emphasizing the importance of IMP preservation, until our recently published IMP-NSM technique and results, the literature is characterized by a paucity of studies reporting the specific success rate of IMP preservation and its impact on ischemic complications.1, 12, 13

IMP-NSM requires a clear margin at the nipple similar to any NSM, and the main contraindication is cancer involving the nipple or the need to remove the nipple to obtain clear margins.21 Therefore, the IMP-NSM technique includes a subnipple biopsy for intraoperative evaluation with frozen section or scrape preparation. If pathology demonstrates cancer at the subnipple biopsy margin, nipple excision is performed and the procedure converted to an ASM (Figure 2). Even following nipple excision, the aesthetic appearance of ASM, which preserves the shape and pigmentation of areolar skin, is superior to NAC removal. Extremely rare contraindications for IMP preservation include angiosarcoma or malignant phyllodes if wide excision is required near the IMP for margins, occurring in < 1% of patients.

IMP-NSM incision location options are similar to conventional NSM, with IMF being most common, followed by radial or vertical incisions with periareolar extensions as needed.1, 13 However, periareolar incisions are avoided if possible due to the higher incidence of NAC necrosis.22, 23 Peritumoral incisions, can be incorporated into the mastectomy incision, or planned to resect skin overlying the cancer for clear margins. Vertical incisions may be a good aesthetic and practical option for patients with ptosis, who have not undergone reduction mammaplasty, or utilizing the prior vertical or IMF scar following prior breast reductions.1, 12, 13 Vertical mastopexy incisions are performed less commonly, in 5% of IMP-NSM, as an option to correct ptosis, which includes periareolar de-epithelialization to raise the NAC more superiorly.1, 13 The final decision regarding incision location is based on cancer location for the best oncologic approach. Additional considerations are prior scars and a discussion with the plastic surgeon to ensure the best aesthetic outcome.

For significant ptosis or macromastia not permitting initial NSM due to nipple location, initial mastopexy or breast reduction, combined with lumpectomy if indicated, can be offered initially, to prepare the breast shape and nipple position for future NSM (Figure 5).1, 2326 We have demonstrated that this approach successfully allows nipple preservation in patients with ptosis, macromastia, or obesity with mean BMI=35, that were not previously routinely offered NSM.23, 25 For mastopexy or breast reduction prior to NSM, the key principle to prevent skin flap or NAC necrosis according to Spear, is keeping the “periareolar dermis intact to preserve the maximum cutaneous NAC blood supply.”24 IMP-NSM preserves maximum NAC blood supply based on MRI blood flow patterns, which may be especially important following prior breast reduction or other breast surgery. Therefore, initial mastopexy or oncoplastic breast reduction, with or without lumpectomy, followed by IMP-NSM with breast reconstruction, facilitates successful nipple preservation for very large or ptotic breasts that would not otherwise be candidates for NSM.

Figure 5. From left to right: A) Preoperative photo showing marked ptosis. Desires bilateral NSM for BRCA2 gene mutation. B) Following reduction mammaplasty, first stage, for planned NSM 3 months later. C) Postoperative, 6 months following bilateral IMP-NSM with immediate autologous reconstruction with free abdominal flaps. Patient has light touch sensation from the sternal border medially for 5 cm on right breast and 8 cm on left breast, indicating sensory nerve preservation of the ACBs of the ICNs.

Cancer location close to the skin requiring skin excision or prior breast scars, are not contraindications to IMP-NSM. However, utilizing previously irradiated lumpectomy scars for NSM has been associated with increased mastectomy skin necrosis and previously not recommended; however, with IMP-NSM, it has been successfully performed without ischemic complications.27 For patients with prior breast scars that are small or farther from the NAC, and not expected to cause NAC ischemia, IMP-NSM is routinely performed without a prior delay procedure. Figure 6 demonstrates a patient with a prior upper inner quadrant lumpectomy scar, and results following single stage bilateral IMP-NSM with abdominal free flap breast reconstruction, without ischemic complications. Thus, most prior breast scars away from the NAC do not require a nipple delay procedure prior to IMP-NSM.

Figure 6. From left to right: A) Preoperative breast MRI MIP demonstrating the IMP blood supply to the NAC. B) Preoperative photo demonstrating the prior lumpectomy scar in the upper inner quadrant and cancer site marked. Bilateral total mastectomies were recommended at an outside hospital due to ptosis; however, the patient desired NAC preservation. C) Postoperative photo at 3 months following bilateral IMP-NSM (vertical incision) with bilateral free abdominal flaps.

A nipple delay procedure, which consists of elevation of the entire NAC with sub-nipple biopsy, possibly with lumpectomy, is performed prior to IMP-NSM for specific indications with anticipated increased risk of necrosis (Table 1). These include oncologic reasons such as in cases of imaging abnormalities very close to the nipple. Additional indications are an anticipated need for subcutaneous excision to obtain clear margins, the need for periareolar incisions interrupting blood supply to the NAC, planned mastopexy mastectomy incisions, or prior RT. A two-stage procedure with nipple delay prior to NSM has been shown to improve NAC and nipple viability after NSM by decreasing necrosis complications.28, 29 A two-stage procedure, with initial lumpectomy and delay procedure is oncologically safe with the majority of patients undergoing the completion NSM, without residual invasive disease on final pathology.30 However, other than the above indications, standard IMP-NSM, typically with IMF, radial or vertical incisions does not require a routine nipple delay procedure; yet, it is associated with a very low postoperative necrosis rate requiring NAC removal in only 0.9% of cases.13 Other than the oncologic reasons above, our main indications for nipple delay procedure for IMP-NSM are prior breast scars or incisions expected to cause significant ischemia, or prior RT, similar to the indications described by Guliano et al.28 However, by preserving the dominant vasculature, IMP-NSM is performed without the need for additional nipple delay surgery in most patients.

Table 1: Indications for initial nipple delay procedure with subnipple biopsy prior to IMP-NSM.

| Indications for nipple delay procedure with subnipple biopsy (Nipple Delay-bx) |

Comments |

| Imaging abnormalities < 1 cm to nipple |

Consider sub-nipple biopsy during IMP-NSM vs. nipple delay-bx |

|

Oncologic concerns (i.e. cancer close to skin in large area) |

Consider lumpectomy with possible skin excision first to assess margins, followed by delayed IMP-NSM |

| Anticipate significant increased risk for ischemia due mastectomy skin incision or prior scars | Consider nipple delay-bx prior to IMP-NSM for mastopexy type mastectomy incision or some large periareolar incisions needed. |

| Prior whole breast RT |

Recommend performing nipple delay-bx |

Nipple Delay-Bx: Nipple delay procedure with retroareolar dissection and subnipple biopsy performed similar to NSM dissection, typically with elevation of the mastectomy flap to just outside the NAC prior to NSM.

The dominant IMP NAC blood supply most commonly emanates at the 2nd or 3rd ICS along the sternal border and is preserved during IMP-NSM. In addition, smaller IMP vessels are often identified and preserved during surgery at the 4th–5th ICS which contribute blood supply to the mastectomy skin and/or NAC.31 Dissection at the 4th ICS near the sternal border is especially important, based on a recent meta-analysis of NAC and breast innervation by Tuinder et al, demonstrating that the anterior cutaneous sensory nerve exiting at the sternal border and lateral cutaneous branch of the 4th ICN are the most important to preserve during breast surgery, as these supply the largest surface of breast skin and NAC.14 Importantly, these ACBs of the 3rd and 4th ICNs are often observed exiting at the sternal border as a neurovascular bundle with the IMP, and thus can be preserved during IMP-NSM (Figures 3 and 5). The IMP-NSM technique currently includes dissection along the sternal border at all ICS exposed during mastectomy for preservation of the IMP vessels and associated sensory nerves for sensory preservation.

Outcomes following IMP-NSM procedure have been very favorable for patients undergoing autologous reconstruction (Figure 5) or implant-based reconstruction (Figure 7). As previously published, following IMP-NSM, nipple or skin necrosis rates were low, with the majority healing without further surgery.1 Therefore, indocyanine green fluorescence angiography to assess mastectomy flap perfusion for intraoperative excision is not routinely utilized for IMP-NSM, since postoperative necrosis excision is uncommon with preservation of blood supply.32 The use of tumescence solution not only helps develop the correct tissue planes, but also minimizes blood loss. Surgeon placed PEC blocks result in effective pain control and resultant marked reduction in the need for narcotic intake.

Figure 7. Left) Preoperative photo. Right) Postoperative following bilateral IMP-NSM and staged prepectoral implant-based reconstruction. Patient reports some light touch sensation of the medial breast, including nipple sensation bilaterally, indicating sensory preservation of ACBs of the ICNs.

Future studies could evaluate if breast MRI blood flow patterns could be useful in surgical planning for incision type or help determine indications for nipple delay procedures for patients at higher risk of necrosis. Selecting appropriate patients that would benefit from a nipple delay procedure prior to IMP-NSM, and the effect of different types of MRI blood flow patterns on the decision about incision placement, remain areas in which future studies could be very informative. Furthermore, IMP-NSM appears to preserve sensation in the medial breast based on the anterior cutaneous sensory nerves observed at surgery that are preserved with the IMP neurovascular bundle, and preliminary results indicating corresponding preserved sensation, which is being studied further to assess the effect on sensory preservation.

IMP-NSM represents an important updated surgical technique to intentionally preserve the IMP and can be easily performed to decrease ischemic complications. Patients with significant ptosis or macromastia that would not otherwise be candidates for NSM, are offered initial mastopexy or breast reduction, followed by IMP-NSM with reconstruction for improved aesthetics associated with nipple preservation. Preserving the IMP vessels near the sternal border improves NAC and skin vascular supply, resulting in very low ischemic complications and excellent clinical outcomes, with the added benefit of associated sensory nerve preservation. Thus, IMP-NSM can be routinely performed to improve clinical outcomes.

Follow-up

All patients underwent initial follow up postoperatively by the breast surgical oncologist every 3–6 months, and additional follow up with the plastic surgeon.

Equipment

No special equipment other than routine surgical instruments are needed for NSM.

Disclosures

No relevant disclosures.

Statement of Consent

The patient referred to in this video article has given their informed consent to be filmed and is aware that information and images will be published online.

Addendum

The video was updated on 10/20/23 to add the split-screen image during chapter 9 of the IMP, and for an additional label at the end for the PECs 2 block.

Citations

- Karin MR, Pal S, Ikeda D, Silverstein M, Momeni A. Nipple sparing mastectomy technique to reduce ischemic complications: preserving important blood flow based on breast MRI. World J Surg. 2023;47(1):192-200. doi:10.1007/s00268-022-06764-x.

- Wong SM, Chun YS, Sagara Y, Golshan M, Erdmann-Sager J. National patterns of breast reconstruction and nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer, 2005–2015. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26(10):3194-3203. doi:10.1245/s10434-019-07554-x.

- Krajewski AC, Boughey JC, Degnim AC, et al. Expanded indications and improved outcomes for nipple-sparing mastectomy over time. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3317-3323. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4737-3.

- Didier F, Radice D, Gandini S, et al. Does nipple preservation in mastectomy improve satisfaction with cosmetic results, psychological adjustment, body image and sexuality? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118(3):623-633. doi:10.1007/s10549-008-0238-4.

- Satteson ES, Brown BJ, Nahabedian MY. Nipple-areolar complex reconstruction and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gland Surg. 2017;6(1):4-13. doi:10.21037/gs.2016.08.01.

- Wei CH, Scott AM, Price AN, et al. Psychosocial and sexual well-being following nipple-sparing mastectomy and reconstruction. Breast J. 2016;22(1):10-17. doi:10.1111/tbj.12542.

- Ahn SJ, Woo TY, Lee DW, Lew DH, Song SY. Nipple-areolar complex ischemia and necrosis in nipple-sparing mastectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(8):1170-1176. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.006.

- Bahl M, Pien IJ, Buretta KJ, et al. Can vascular patterns on preoperative magnetic resonance imaging help predict skin necrosis after nipple-sparing mastectomy? J Am Coll Surg. 2016;223(2):279-285. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.04.045.

- Agha RA, Al Omran Y, Wellstead G, et al. Systematic review of therapeutic nipple‐sparing versus skin‐sparing mastectomy. BJS Open. 2019;3(2):135-145. doi:10.1002/bjs5.50119.

- Galimberti V, Vicini E, Corso G, et al. Nipple-sparing and skin-sparing mastectomy: review of aims, oncological safety and contraindications. The Breast. 2017;34:S82-S84. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2017.06.034.

- Karin M, Pal S, Silverstein M. Nipple sparing mastectomy with internal mammary artery perforator preservation based on breast MRI reduces ischemic complications. In: The American Society of Breast Surgeons Official Proceedings. Vol XXIII. 29; 1-330. Ann Surg Oncol; 2022.

- Karin MR, Momeni A. Contemporary nipple-sparing mastectomy technique to preserve the internal mammary perforator blood flow to the nipple and analysis of outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235(5). doi:10.1097/01.XCS.0000895632.71287.67.

- Karin MR, Wu R, Black CK, Momeni A. Utilizing breast MRI blood flow data to improve clinical outcomes following skin sparing mastectomy and nipple sparing mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;233(5):e13. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.08.037.

- Smeele HP, Bijkerk E, van Kuijk SMJ, Lataster A, van der Hulst RRWJ, Tuinder SMH. Innervation of the female breast and nipple: a systematic review and meta-analysis of anatomical dissection studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150(2):243-255. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000009306.

- Edquilang J, Wu R, Momeni A, Karin MR. Outcomes after preservation of the internal mammary artery perforator in nipple-sparing mastectomy. Springer. 2020:S441-442.

- Karin M, Edquilang J, Momeni A. Use of breast MRI to facilitate identification and preservation for the dominant internal mammary perforator blood flow to the nipple in nipple-sparing mastectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(S1):12-13.

- Khavanin N, Fine NA, Bethke KP, et al. Tumescent technique does not increase the risk of complication following mastectomy with immediate reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(2):384-388. doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3311-0.

- Tasoulis MK, Agusti A, Karakatsanis A, Montgomery C, Marshall C, Gui G. The use of hydrodissection in nipple- and skin-sparing mastectomy: a retrospective cohort study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7(11):e2495. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002495.

- Urban C, Rietjens M, El-Tamer M, Sacchini VS, eds. Oncoplastic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery. Springer International Publishing; 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-62927-8.

- Maggi S, Amanti C, Lombardi A, et al. Importance of perforating vessels in nipple-sparing mastectomy: an anatomical description. BCTT. Published online July 2015:179. doi:10.2147/BCTT.S78705.

- Coopey SB, Smith BL. The nipple is just another margin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3764-3766. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4648-3.

- Tevlin R, Griffin M, Karin M, Wapnir I, Momeni A. Impact of incision placement on ischemic complications in microsurgical breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149(2):316-322. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008770.

- Momeni A, Kanchwala S, Sbitany H. Oncoplastic procedures in preparation for nipple-sparing mastectomy and autologous breast reconstruction: controlling the breast envelope. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(4):914-920. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006657.

- Spear SL, Rottman SJ, Seiboth LA, Hannan CM. Breast reconstruction using a staged nipple-sparing mastectomy following mastopexy or reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(3):572-581. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e318241285c.

- Daly L, Tsai J, Stone K, et al. Nipple‐areola‐complex preservation and obesity—successful in stages. Microsurgery. Published online April 3, 2023:micr.31043. doi:10.1002/micr.31043.

- Salibian AA, Frey JD, Karp NS, Choi M. Does staged breast reduction before nipple-sparing mastectomy decrease complications? A matched cohort study between staged and nonstaged techniques: Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(5):1023-1032. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000006121.

- Frederick M, Lin A, Neuman R, Smith BL, Austen W, Colwell AS. Nipple-sparing mastectomy in patients with previous breast surgery: comparative analysis of 775 immediate breast reconstructions. Breast Diseases: A Year Book Quarterly. 2016;27(1):55-57. doi:10.1016/j.breastdis.2016.01.014.

- Jensen JA, Lin JH, Kapoor N, Giuliano AE. Surgical delay of the nipple–areolar complex: a powerful technique to maximize nipple viability following nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(10):3171-3176. doi:10.1245/s10434-012-2528-7.

- Ju T, Chandler J, Momeni A, et al. Two-stage versus one-stage nipple-sparing mastectomy: timing of surgery prevents nipple loss. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(10):5707-5715. doi:10.1245/s10434-021-10456-6.

- Thompson C, Chandler J, Ju T, Wapnir I, Tsai J. Two-stage nipple-sparing mastectomy does not compromise oncologic safety. Springer. 2022;29(1):204-205.

- Nahabedian MY, Angrigiani C, Rancati A, Irigo M, Acquaviva J, Rancati A. The importance of fifth anterior intercostal vessels following nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149(3):559-566. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008828.

- Liu EH, Zhu SL, Hu J, Wong N, Farrokhyar F, Thoma A. Intraoperative SPY reduces post-mastectomy skin flap complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019 Apr 25;7(4):e2060. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002060.